When you invest in a listed company, there are all sorts of risks that you run: ranging from the systematic risk of the share market to a wide variety of more specific risks – such as financial risk (the risk of the company getting into financial difficulties); business risk (the possibility that the company will make a mistake in its business); product risk (the possibility that the company’s products may fail) technical risk (when the company’s technology proves difficult to bed down or simply doesn’t work) and expansion risk, when an attempt to expand, particularly into another country or market, comes unstuck.

But one risk that flies under the radar is management risk in the non-business sense – the risk that managers will make a mistake not related to the business.

People are human, and a company is only a collection of humans. And humans can be quirky individuals – and say and do silly things.

In April 2022, trans-Tasman chemical manufacturing and logistics company DGL Group (the initials stand for ‘dangerous goods logistics,’ which listed on the ASX in May 2021 as a joint listing with the New Zealand Exchange in its home country, was flying high. Listed in Australia at $1, the stock had soared to $4.09 in just less than 12 months, after a string of profit upgrades.

A few weeks later, founder, chief executive officer (and largest shareholder, with 54% of the stock) Simon Henry was being interviewed by New Zealand’s National Business Review, for that publication’s Rich List. Henry was asked about the relative success of his IPO compared to ASX-listed, Kiwi domiciled meal kit business My Food Bag. While he made some valid criticisms of how My Food Bag’s founders and private equity backers had taken much of the proceeds and not invested much back into the business, the competitive Henry proceeded to lose the plot, in commenting on New Zealand celebrity chef, My Food Bag co-founder and brand ambassador Nadia Lim, who was pictured on page 36 of the company’s prospectus.

Henry said: “I can tell you, and you can quote me, when you’ve got Nadia Lim, when you’ve got a little bit of Eurasian fluff in the middle of your prospectus with a blouse unbuttoned showing some cleavage, and that’s what it takes to sell your scrip, then you know you’re in trouble.”

There was outrage on both sides of the Tasman, with the comments condemned as racist, sexist, and completely irrelevant to the topic of My Food Bag’s share market performance. The New Zealand Race Relations Commissioner and Prime Minister Jacinta Ardern weighed in with criticism. The DGL board was forced to respond by condemning the comments and saying it would “conduct a thorough review into the firm’s culture.”

But while the reputational damage was severe, the real damage was done to where all companies are vulnerable: the actual business, and how it was perceived – and valued – in the marketplace. At least two New Zealand fund managers blacklisted the company. Melbourne-based water treatment and chemical distribution company Ixom, which had been described as a cornerstone customer in DGL’s prospectus, said Henry’s comments were unacceptable.

“Ixom is aware of the comments made by Mr Henry and shares the view of the DGL Board that they are inappropriate, unacceptable and offensive,” the company said in a statement. “Ixom is communicating its serious concern about Mr Henry’s conduct to the DGL Board and is seeking further information from the Board about DGL and Mr Henry’s response.”

The upshot of the fracas was that DGL lost 32% of its market valuation in 15 trading days after the interview was published — for a gaffe not connected to its business.

That is extremely damaging and frustrating for a shareholder.

Later, in September 2022, DGL had another disaster, when, in announcing what were quite good results for the financial year 2022 (FY22), the company said in its outlook statement that while it achieved some “opportunistic growth” in earnings in FY22, that was “unlikely to be replicated to the same extent in FY23″. DGL warned that as a result of outsized growth in FY22 and industry-wide inflation, “the Group anticipates its earnings growth to flatten in FY23.”

That news caused the company to lose almost half of its market capitalisation in just three days. It was cold comfort to shareholders but at least it was a business issue. DGL is now battling cost inflation and further profit downgrades and has been de-rated by almost half from the price/earnings (P/E) ratio it commanded before its fall from grace. At 76 cents, the shares are down more than 81% from the price prior to Henry’s ill-fated interview about My Food Bag. The reaction to those comments doesn’t explain the full demotion of the stock – but it certainly didn’t help the valuation.

In January 2022, global building materials company James Hardie sacked its chief executive Jack Truong, with immediate effect, after an inquiry found he had acted inappropriately for intimidating, threatening and humiliating his senior managers. James Hardie said the board had received reports from employees in the months leading up to its action, about Truong’s work-related interactions.

The company said it hired a third party to help investigate the claims and had worked with Truong, who was appointed in 2017, to change his behaviour.

When he did not alter his behaviour and executives threatened to leave, the board decided to remove the CEO – who was terminated with nothing more than his statutory entitlements, a quite brutal sacking in comparison with how these situations normally play out.

During a briefing with analysts, James Hardie executive chairman Mike Hammes said Truong’s behaviour had been so bad, it had threatened the stability of the executive team: feedback from a confidential survey told the company that its work environment had become overtly hostile, with the majority of respondents reporting inappropriate behaviour. Several executives told the company that they intended to resign or were actively considering doing so as a direct result of Truong’s actions.

Hammes told the analysts that Truong had started, over the last few months, “treating people with a lack of respect, using intimidation, fear and humiliation, and it was not a one-off. We could not accept that.”

The company offered coaching to Truong, but he didn’t alter his behaviour and refused to accept the need to change. James Hardie bit the bullet and removed its CEO.

The announcement triggered a near-$1 billion fall in the company’s market value: the shares fell almost 50% in six months. Not all of that can be laid at the door of the CEO termination, but it was a major contributor. And James Hardie – while it is performing well at present – remains well short (16% short) of where it was trading when the company made the difficult decision to get rid of its CEO.

My last example (there were many to pick from) is the strange story of Geoff Bainbridge, chief executive and managing director of Tasmanian-based Lark Distilling, and co-founder of the burger chain Grill’d. In February 2022, The Australian newspaper alerted Bainbridge to the existence of a video of him smoking an illicit drug in his underwear, while making sexually explicit comments. The newspaper agreed not to publish the material until Bainbridge was able to respond, but the Lark board began a formal investigation. Bainbridge, Lark’s fifth-biggest shareholder with a stake valued at more than $13 million, resigned, but claimed the video had been taken in 2015 – before he joined Lark Distilling in mid-2020 – while he was travelling in South-East Asia, as part of an extortion attempt by un-named criminals.

The board of Lark Distilling, which was valued at $340 million at the time, held an emergency board meeting about Bainbridge, and the company announced that Bainbridge had resigned “effective immediately to enable him to manage a personal matter that was brought to the attention of the board on the afternoon of 15 February 2022.” Then non-executive director Laura McBain, former chief executive of infant formula exporter Bellamy’s, took over as interim managing director; subsequently global beverages executive Satya Sharma was named chief executive in November 2022, taking over in May 2023.

Mr Bainbridge said he had paid the extortionists, engaged with a London-based threat assessment agency and stopped replying to the blackmailers, who soon released the videos to the media. But it soon emerged that the video that The Australian had was filmed in the Middle Park (Melbourne) home that Bainbridge bought in August 2020.

(The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald published articles that suggested Bainbridge was the victim of an elaborate extortion sting, but later took those articles down, admitting they appeared to have been “badly misled” after doubts were raised about aspects of his story.)

Lark, which had traded as high as $5.44 in October 2021, fell by 21% in a day when Bainbridge’s resignation was announced in February 2022, and by one-third in a month. (That was painful to me: I had recommended Lark Distilling in Switzer Report on 10 January as having “good upside from current levels.”)

From $4.55 when The Australian told Bainbridge it had the video, in February 2022, Lark Distilling is now down by 69%.

The company is being hit by slowing consumer spending on high-end products: it has told the market it expects net sales for the 12 months ended June 30 will be about $17 million down from $20.3 million for 2021-22. Sales for the June half of 2022-23 are on track for a result of about $7.4 million, compared with $9.6 million in the December half.

Under Sharma, Lark has closed some “non-core” operations and is undertaking a strategic review, with the strategic direction of the whisky business to be detailed to the market by October. Lark’s brands include Lark and Nant whisky, Forty Spotted Gin, and handcrafted Tasmanian spirits and liqueurs, such as Quiet Cannon Rum and XO Brandy: about 80% of Lark’s sales are in Australia, and the company says it wants to boost overseas sales. The company has a whisky bank of close to 2.4 million litres, which is still maturing and will feed into sales over the next decade.

Lark believes it is also suffering from a slump in risk appetite among investors in smaller ASX companies. It is more likely that investors need to see a clear pathway to an export market: buying the Pontville Distillery and Estate near Hobart, for $40 million, in October 2021 (its third distillery) was a key plank in building the export capability, and the company is currently exporting into China, Vietnam, Thailand and Singapore. The whisky bank supports the export plans, but investors need to see this strategy spelled out in greater detail.

Lark is a different company from the one let down by CEO behaviour in early 2022 – it is much wiser about people and culture – but it is also a less valuable one.

So is DGL Group; and so is James Hardie.

I stress that there is more to the lower current valuation than the CEO behaviour, but the point is that such a risk is part and parcel of share investing, although one would like to think it is still a rare occurrence. Investors who encounter this kind of problem need to decide whether to keep the shares — whether the revelations make the business a different business, or whether they are going to be a short-term issue buffeting the share price.

For the record, I would be comfortable buying Lark Distilling at $1.41; James Hardie at $46.47; and DGL Group at 76.5 cents, although none is a dividend-payer. Each of them hit turbulence in the form of poor CEO behaviour, and they will not be the last ASX stocks to suffer this. The changing business environment has also been tough on them, in different ways specific to their respective businesses, but certainly, the CEO gaffes didn’t help. Unfortunately, the people who run the companies in which we invest are only human, and the risk inherent in human behaviour can never be ruled out as a risk that could affect your investments.

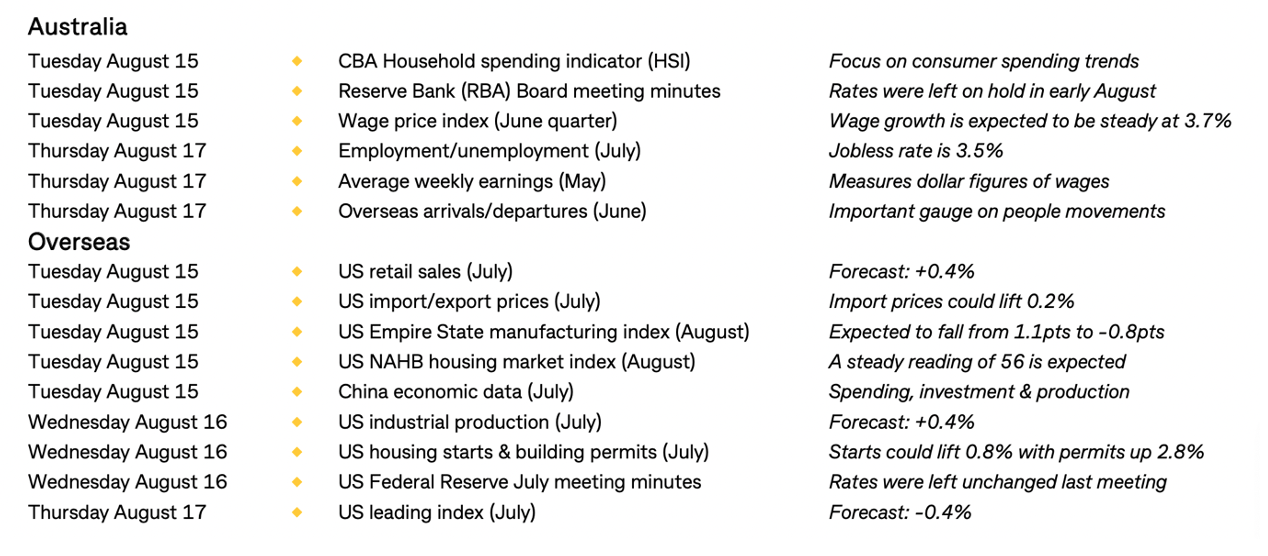

Oops! Apologies, we put the wrong Week Ahead table in last Saturday so here it is below:

Important: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. Consider the appropriateness of the information in regards to your circumstances.