The uranium price has had a good few years, leaving the doldrums of a sub-US$25 a pound price, which prevailed for most of the mid-2010s, in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, far behind. It was still under US$25 a pound two years ago, but the market was starting to face supply shortages even then.

Subsequently, global geopolitical events affecting producer countries Kazakhstan and Russia, as well as a reassessment globally of the role of nuclear energy as providing a low-emission source of baseload electricity, have lifted uranium demand, and the price has responded.

In April, uranium surged almost to US$65, a price it had not seen for 11 years. Worries about Russian supply and recession fears (which could lower energy demand) have brought the price back to US$47.85, but analysts see the demand picture as being very positive for the price over the longer term. It is widely considered that the uranium price needs to be maintained in the US$50 to US$60 range for a sustained period before a lot of existing production capacity – and new projects – becomes economical again.

According to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), there are about 440 nuclear power reactors operating in 33 countries, with a combined capacity of about 390 gigawatts (GW). In 2020 these provided 2553 terrawatt hours (TWh,) about 10% of the world’s electricity. About 55 power reactors are currently being built, in 19 countries, notably China, India, Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

Uranium consumption has returned to pre-2011 levels, and requirements are expected to continue to grow. For example, it is expected that China will approve six to eight new reactors each year, with six new reactors approved in April 2022. On the back of the increased activity, by 2040, global uranium demand is expected to increase by 47% from 2020 levels.

In June, the Biden Administration proposed a US$4.3 billion ($6.1 billion) plan to move away from Russian uranium imports – this proposal will benefit producers in friendly countries. The US is the world’s largest producer of nuclear power, accounting for roughly 20% of domestic electric output. Russia imports accounted for 23% of the enriched uranium required to power US nuclear reactors in 2020.

As well, the recent World Nuclear Fuel Cycle conference in London heard that uranium inventories are precariously low: uranium fuel inventory levels for US nuclear utilities are at just 16 months of requirements – below the recommended two-plus years minimum.

Another positive factor is the growing role of investment players such as Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT), which has bought more than 32 million pounds of uranium on the spot market since September 2021.

All these factors are coalescing into strong drivers for uranium. This picture affects Australia because, despite not using nuclear energy, the country has the world’s largest reserves of uranium and more than one-third of the world’s total reserves. Australia is the third-largest producer of uranium, behind Kazakhstan and Canada, producing about 7,000 tonnes a year of exported uranium from three mines: BHP’s Olympic Dam and Heathgate Resources’ (a subsidiary of US company General Atomics) operation in the north of South Australia, and Energy Resources of Australia’s (ERA’s) Ranger mine in the Northern Territory.

The Ranger orebody, discovered in 1969, is the richest in the southern hemisphere. Uranium was mined at Ranger for almost forty years; during that time, Ranger produced more than 132,000 tonnes of uranium oxide.

An underground resource was discovered in 2009. But mining ceased in January 2021: ERA’s major focus now is rehabilitating the mine project area such that it can be incorporated into the world heritage-listed Kakadu National Park – but it is still selling down its inventories of drummed uranium oxide. (ERA, which is 86% owned by Rio Tinto, also owns the world-class Jabiluka deposit in the Northern Territory, one of the world’s largest high-grade uranium deposits, but neither Jabiluka nor the Ranger underground resource looks like ever being mined, given that ownership has been transferred to the traditional owners, and the deposits are within Kakadu National Park.

Perth-based Paladin Energy (PDN) owns 75% of the Langer Heinrich project in Namibia, which was mothballed because of low prices back in 2018. A globally significant operation, having already produced more than 43 million pounds of uranium oxide to date, Paladin is planning a restart at a cost of $81 million, targeting 5.9 million pounds of uranium oxide a year at peak production. In Australia, Paladin also wholly owns two advanced uranium exploration projects, at Mount Isa in Queensland and Manyingee in Western Australia; in Canada, the company owns a 60% interest in the Michelin deposit in Labrador, one of the largest uranium deposits in North America.

There is a large contingent of uranium stocks on the ASX – but here are three, with positive stories on different continents, that I think look like great speculative buys at these prices.

1. Boss Energy (BOE, $1.975)

Market capitalisation: $696 million

12-month price-performance: 54.3%

Analysts’ consensus price target: $3.20 (Thomson Reuters, four analysts), $3.20 (FNArena, one analyst)

Boss Energy (BOE) owns the idle Honeymoon uranium mine at Kalkaroo in South Australia, which was for a short time Australia’s fourth operating mine – and is poised to grab that title again. Between 2011 and 2013, under different ownership, Honeymoon yielded 312 tonnes of uranium, but in 2013 high costs saw it shut down. The operating company was bought by Boss Resources in 2015, and subsequently Boss negotiated native title agreements and operational permits – and earlier this month, the company announced the Final Investment Decision (FID) to develop Honeymoon. The project is fully-funded, with no debt, meaning Boss will now accelerate engineering, procurement and construction, with production set to start in the December quarter of 2023, ramping up to 2.45 million pounds of uranium oxide within three years.

Boss announced in 2020 that it had developed technology to lower the operating costs at Honeymoon; and predicts its average all-in sustaining cost (AISC) – a figure that incorporates not only the “cash cost” of production but all the costs that allow production to be sustained – over the initial 11-year mine-life to be about US$25.60 a pound. The company says there is good potential to extend that mine-life figure through “satellite” deposits near the mine. The company also holds a 1.25 million-pound uranium stockpile valued at US$59.4 million ($84.8 million), based on a spot price of US$47.50 a pound, as at 31 May 2022.

The enhanced feasibility study on Honeymoon states that at a uranium oxide price of US$60 a pound, Honeymoon would need US$80 million ($110 million) in capital expenditure to resume, and would be “economically robust,” with an internal rate of return (IRR) of 47%. Boss says it is “in an extremely strong negotiating position with utilities, and ensures we can capitalise on the looming uranium supply deficit”.

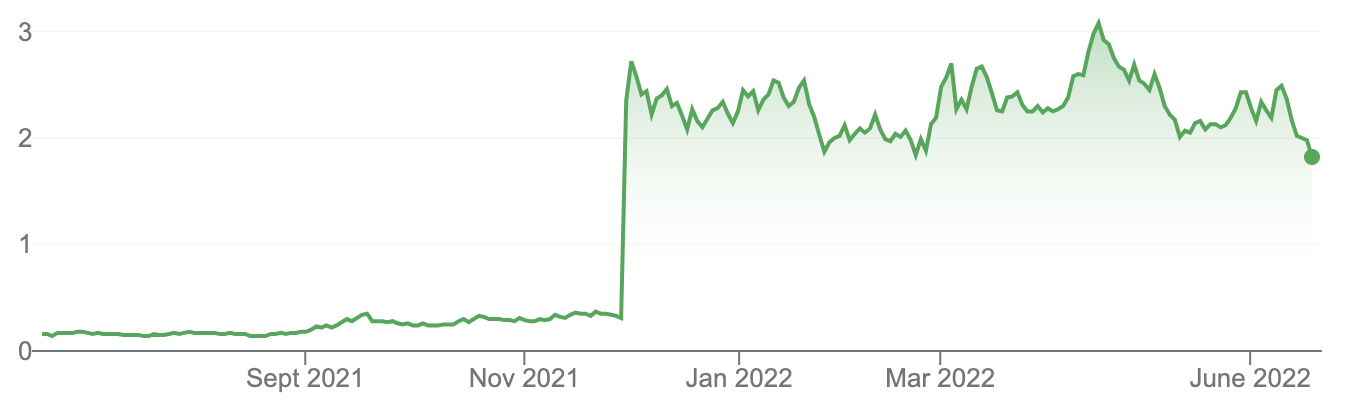

Boss Energy Limited (BOE)

2. Lotus Resources (LOT, 23 cents)

Market capitalisation: $277 million

12-month price-performance: 35.3%

Analysts’ consensus price target: 40 cents (Stock Doctor, three analysts)

Lotus Resources (LOT) owns an 85% stake in the high-grade Kayelekera uranium mine in the African country of Malawi, which produced 11 million pounds of uranium oxide between 2009 and 2014, but was put on care and maintenance in February 2014 because of low uranium prices. Lotus bought its stake from Paladin Energy in June 2019: the remaining 15% is held by the Malawi government.

Earlier this year Lotus upgraded the Kayelekera resource by almost 25%, lifting it to 46.3 million pounds at a grade of 500 ppm uranium oxide, for 37.4 million pounds of uranium oxide. Lotus plans to restart Kayelekera by spending US$75 million in initial capital expenditure: the definitive feasibility study (DFS) is expected later in 2022. Lotus plans an initial 14-year life-of-mine operation, at a cash cost of production of about US$30 a pound. There has been very little exploration around the site in the last 20 years, despite the presence of multiple near-mine targets – so the company is confident of extending the resource and the mine life.

Then there is the Livingstonia project, located 90 kilometres southeast of the Kayelekera mine, which Lotus bought for just US$25,000 ($35,700) in 2021. Livingstonia has similar mineralisation to Kayelekera: earlier this month, Lotus announced an inaugural mineral resource estimate for the Livingstonia deposit, of 6.9 million tonnes grading 320 parts per million uranium oxide. These early figures increase the total resource estimate for the company’s assets in Malawi to 49.4 million tonnes at 475 ppm of uranium oxide, for 51.1 million pounds of uranium oxide. While Livingstonia is not included in the current DFS, Lotus believes there is potential for it to become a satellite operation in the future, once the Kayelekera resource has been depleted. The beauty of Livingstonia is that Lotus bought it for an absolute song: effectively, it paid 4 US cents per pound (contained resource) of uranium oxide.

It’s also worth mentioning that last week, broking firm BW Equities released a research report on Lotus with a share price target of 55 cents.

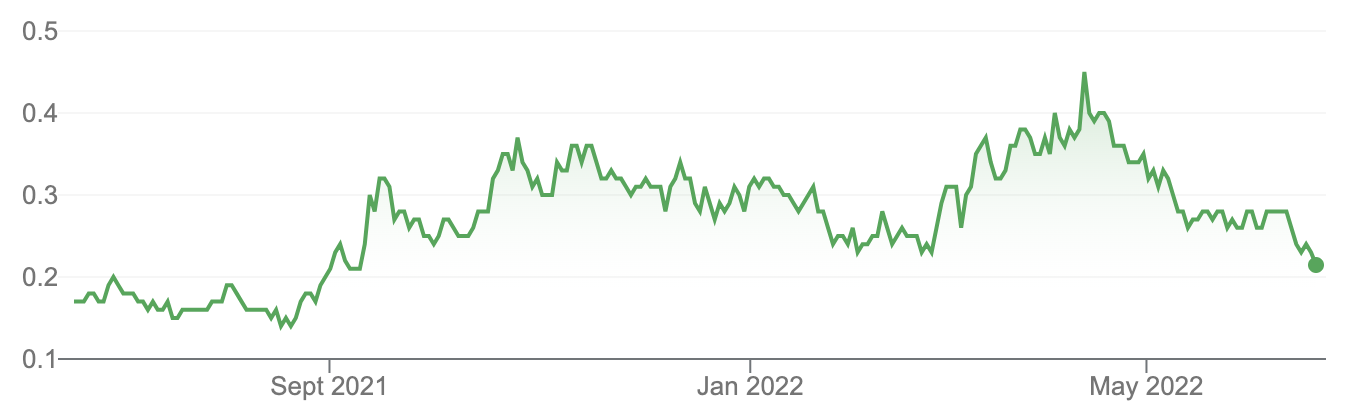

Lotus Resources Limited (LOT)

3. Peninsula Energy (PEN, 16.5 cents)

Market capitalisation: $165 million

12-month price-performance: 3.1%

Analysts’ consensus price target: 41.6 cents (Thomson Reuters, four analysts)

Peninsula Energy (PEN) owns the Lance uranium projects in Wyoming, US, which it is working on fast-tracking to production. While it hasn’t started mining, Peninsula has long-term sales contracts in place, extending to 2030. The company recently started a US$3.4 million ($4.9 million) early preparatory works program at the Lance Project, which has been designed to enable an accelerated restart and ramp-up of production operations, should a final investment decision (FID) be approved: FID is expected by the end of 2022.

Peninsula’s US subsidiary Strata Energy Inc. built Lance, with commercial uranium production operations commencing in 2015. Uranium operations – using an alkaline process – ceased in July 2019, mainly because of lower-than-expected recoveries. Peninsula now proposes to pivot its production method from an alkaline method to a low-pH in-situ recovery (ISR) process, which it says would achieve the operating performance and cost profile of the top quartile (to 25%) of the global industry-leading uranium projects. About 57% of the global uranium produced in 2020 was through the low-pH ISR process. Lance is the only US-based uranium project authorised to use the industry-leading low pH ISR method.

Peninsula proposes to spend US$6 million ($8.6 million) on the transition to the low-pH ISR process, and the re-start of production, which could be achieved within six months of the green light for re-start. Then, the Stage 1 ramp-up, to a capacity of 1.15 million lbs of uranium a year, would need working capital of about US$15 million ($21.4 million) but could be done at an all-in sustaining cost (AISC) of production of US$41 a pound. After that, the Stage 2 expansion, to reach the capacity of 2.3 million pounds of uranium a year, at an AISC of US$31 a pound of uranium, would need capital spending of US$43 million ($61.4 million). The life-of-mine (LOM) of the project is estimated at 17 years.

Peninsula is also sitting on 310,000 pounds of uranium concentrate that it bought on the market in mid-2021: this stash has doubled in value since it was purchased and is now valued at US$63.75 per pound, for a total value of US$19.8 million ($28.3 million). Peninsula is also selling inventory into its long-term contracts with utilities in both North America and Europe; it expects to deliver 450,000 pounds of uranium oxide in 2022. Peninsula is the only junior uranium producer with long-term sales contracts; these sales represent about 15% of projected life-of-mine production from Lance. There is also a high degree of upside exposure through the 310,000-pound kitty of physical uranium.

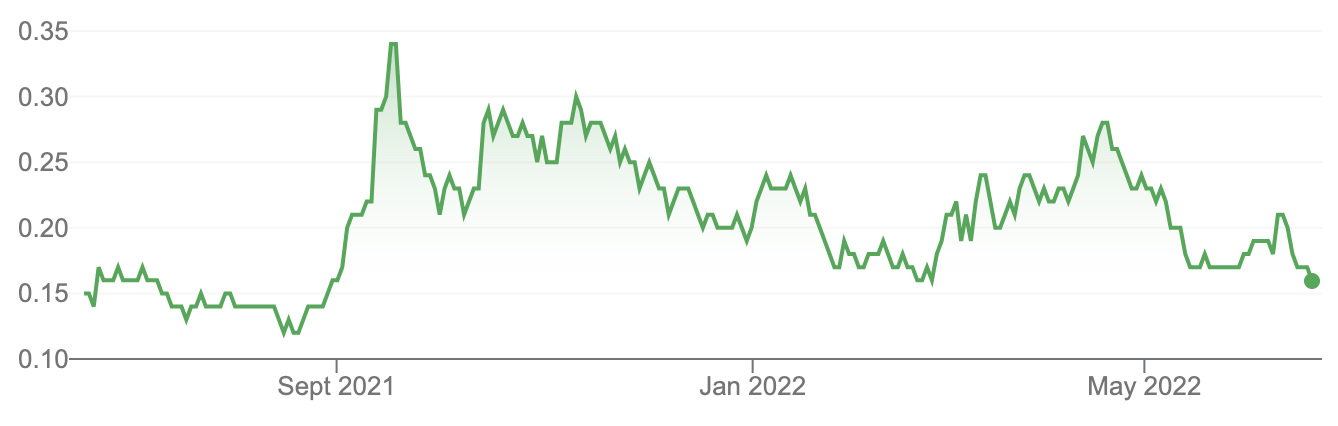

Peninsula Energy Limited (PEN)

Important: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. Consider the appropriateness of the information in regards to your circumstances.