Good asset allocation is the key to good investment. Achieving the right balance of assets in your portfolio can not only help you sleep more soundly at night, but also help best ensure your financial future. To do this, you will need an asset mix that is consistent with your risk tolerance and long-term investment goals.

In a sense, asset allocation is like making wine. Just as a wine maker blends different grape varieties to achieve a flavour appealing to certain tastes, an asset allocator blends different asset types or ‘classes’ to achieve a portfolio risk and return profile that best meets an investor’s needs.

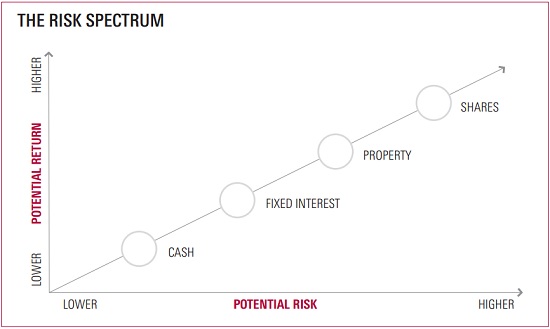

It is generally not possible to boost a portfolio’s expected return without also assuming higher short-run risk or volatility in these returns. That said, a better trade-off between risk and return is possible through good portfolio diversification.

Five key asset classes

All investments within a portfolio can generally be attributed to one of at least five asset classes, which are distinguished by their differing degree of expected risk and return.

Cash: The safest asset class, with virtually zero short-run return volatility, but with the lowest long run expected return. Typical investments within this asset class include bank term deposits or cash management trusts.

Fixed-income securities: Returns are generally a bit higher than that available on cash, though with greater volatility in returns. Typically investments include government bonds or fixed income funds that invest in government and corporate bonds. The uncertainty in returns derives from the fact that rising interest rates tend to reduce the capital return from bonds, whereas falling interest rates boost capital returns.

Property: Returns from this asset class are again generally higher than for fixed income securities because investors get rental yields plus capital growth through rising property values. Risks, however, are also higher because property values can fluctuate in line with the economy and interest rates. Property exposure can be held directly or indirectly through listed or unlisted property investment funds. Note: managed property funds typically provide exposure to commercial property (ie. offices, shops and factories) rather than residential properties.

Domestic Shares: Further up the risk and return spectrum than property, this asset class gives investors exposure to local company shares – either directly or through listed and unlisted share investment funds.

International Shares: Although their longer-run returns and risk may be not much different from domestic shares, international shares are typically treated as an alternate – and riskier – asset class than domestic shares, as Australian investors may be less familiar with these markets.

Increasingly, investors and financial advisors are broadening the range of asset classes to include commodities, currencies and hedge funds/private equity groups. Another distinction is sometimes made within the international shares asset class between ‘developed markets’ and ’emerging markets’ (ie. China and India).

Source: Vanguard Investments, Plain Talk Guide.

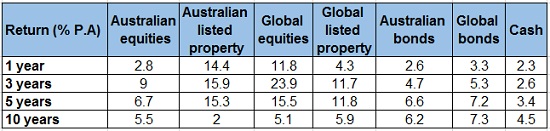

Of course, returns can deviate from longer-run expectations over shorter periods. Over the past 10 years, for example, international shares and listed property have produced relatively low and volatile returns compared with what we might generally expect. Gold prices, by contrast, have increased relatively strongly.

Asset Class Returns to December 2015

Source: Lonsec

Your risk preference

Investors can typically differ in their preference for risk and return depending on their age and psychological risk sensitivity. Generally the older and closer to retirement an investor is, the greater the preference toward lower risk and lower return – and by consequence, asset allocations that favour cash and bonds over equities.

These investors might also display a stronger preference for income over capital returns – or dividends and interest payments they can spend today, over growth in the capital value of shares or property they own.

An investor on the verge of retirement with 100% of their portfolio in highly volatile emerging market equities, for example, has probably got the wrong asset allocation as there is a good risk that returns could fall in the short-term and impinge on their ability to live off their next egg. This investor is taking too much risk given their needs.

Similarly, a young worker with 40 years until retirement should care less about short-run volatility in returns, and has a greater need to ensure long run expected portfolio returns are high enough to meet their retirement goals. Their portfolio allocation should be tilted toward more growth assets such as equities over cash or bonds.

Other considerations that may affect investor preference are their specific knowledge/skills set and pre-existing exposure to other investments. An investor with good knowledge of a certain asset class or specific investments may feel lower risk by investing more in these areas than otherwise. Similarly, an investor that already owns many residential or commercial properties – or listed company shares through executive bonus schemes – might prefer less exposure to these asset classes when setting up a new investment portfolio.

Optimisation and the magic of diversification

Along with blending asset classes to create portfolios that match investor needs, the other key to successful asset allocation is to exploit the benefits of diversification. As the returns from different investments – both within asset classes and between asset classes themselves – are not perfectly correlated, investors can usually achieve a better trade-off between risk and return by holding a range of investments.

Imagine two businesses, for example, with the same strong long-run expected returns from selling ice creams and heaters respectively. The returns from selling ice cream are highly seasonal, and usually come at opposite times of the year to those from selling heaters. So a portfolio that contained both businesses could greatly reduce month-to-month volatility in returns without the need to sacrifice long-run expected performance.

In general, the holy grail of asset allocation is to find investments with high expected return, low expected return volatility, and low correlation in return to other investments within the portfolio. As with ice creams and heaters, the best investments are those with negative return correlation to other assets.

In recent years, relatively low and stable inflation has meant the returns from equities and bonds have tended to be negatively correlated. This is because weak economic growth tends to hurt equities but help bonds and visa versa. This suggests a combination of the two in most case can provide good portfolio diversification. Similarly, the correlation in returns from local and international shares in local Australian-dollar terms is lessened by the often large swings in currencies over time.

Calculating expected returns

When determining the expected returns from an asset class, investors need to be wary of not just relying on recent past performance. Past performance is often a poor predictor of future performance, especially if an asset class has recently experienced a period of above atypical returns due to a bubble or bust.

In what is termed ‘regression to the mean’, sustained periods of above average returns are often followed by periods of below-average returns. Indeed, investors who piled into dotcom stocks at the height of the internet bubble earlier this decade felt the full force of regression to the mean, as did investors who invested strongly in listed property prior to the recent global financial crisis.

Those investing in an asset class based on its recent strong performance are relying on momentum – which is another important, albeit opposing, force to regression to the mean. Typically, relative asset class performance tends to trend for up to several years due to slow moving changes in economic conditions and slow investor responses to them. The interplay of these two duelling forces can result in asset class performance often moving through cycles of over valuation to under valuation and back again.

Thankfully, the longer an investor’s time horizon the less concerned they need be about short-run valuation cycles, as these will have a relatively muted impact on long-run returns. Valuation issues and potential deviations in return performance from their mean become more important as investor time horizons shorten.

Risk – what it is and isn’t

Similar considerations occur when looking at risk. Just because returns to an asset class have not been volatile in recent years, does not mean they won’t be in the future. Indeed, during bubble periods, some asset classes can experience strong returns with relatively little volatility – the latter is a sure sign of trouble ahead.

Similarly, the correlation in returns between assets can also vary over time depending on the type of shocks impacting the economy. In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, returns between bonds and equities were more positively correlated than today, as both were similarly affected by marked swings in price inflation and interest rates. As they better integrate into the global economy, stocks in emerging markets are generally becoming more closely correlated with those of developed markets.

Risk also depends on an investor’s time frame. Year-to-year volatility in returns should matter less to someone with a 40-year investment outlook compared with someone who relies on yearly returns to fund current retirement needs. For long-term investors, the greater risk is shortfall risk – or the risk that their long run returns won’t be high enough to meet their goals.

Even investors with more intermediate investment time frames – such as five years – should appreciate that the volatility in five-year returns from the share market, for example, is considerably less than that of annual returns. Indeed, it is vary rare for the share market to produce a negative return over a five-year period, even when bear market downturns have intervened.

Strategic vs tactical asset allocation

Portfolio construction tailored to an investor’s long-run investment goals – and typically based on the long-run expected returns from each asset class – is known as ‘strategic asset allocation’. Strategic asset allocation should be the building block of any investor’s investment strategy. At its core, it relates to ensuring younger investors have enough growth assets in their portfolio, and older investors have enough defensive and income producing assets.

More contentious is the use of ‘tactical asset allocation’, which varies portfolio exposure over the short-run to take into account anticipated deviations in asset-class performance from their long-run mean. As noted above, asset classes can often moves through cycles of strong above average and then below average return.

Within a portfolio construction context, deciding on strategic versus tactical allocation really boils down to what you consider to be an appropriate time horizon and your choice of expected returns. An investor who cares little about short-run return variations in returns can base portfolio construction on long-run expected returns and risk for each asset class. Those that engage in tactical allocation effectively try to maximise expected returns over shorter time horizons.

Portfolio Construction

Having decided on the range of asset classes to be considered, and their expected risks and returns, portfolios can then be constructed or optimised to achieve the highest expected returns for given levels of overall portfolio risk. An example of such a range in asset allocations is provided below. Note how exposure to riskier assets such as equities – which have higher expected long-run returns – increases as allowable portfolio risk also increases.

Indicative Target Asset Allocations by Risk Profile

[table “20” not found /]Important information: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. For this reason, any individual should, before acting, consider the appropriateness of the information, having regard to the individual’s objectives, financial situation and needs and, if necessary, seek appropriate professional advice.