Financial commentators are paid to spot big turning points in financial markets. But few ever pick the absolute trough or peak in asset prices. It’s a question of timing. That is, how early or late one is to a turning point. Buy too early and you risk further falls. Buy too late and you miss much of the recovery.

Softer-than-expected economic data in the United States this month sparked talk of a major turning point for interest rates. A dovish sounding US Federal Reserve and weaker (but not too weak) jobs growth buoyed markets.

So, too, did calls from Middle East leaders for a de-escalation of the Israel/Palestine conflict. The Brent Crude oil price hit its lowest level in a month as market fears of oil-supply disruption from the Middle East eased. That’s good for inflation and supports the view that higher US rates won’t be needed.

The news was amplified in the bond market. The yield on the US 10-Year Treasury, a vital economic benchmark that affects other interest rates, is down from almost 5% in mid-October to 4.586%. In bond-market terms, that’s a decent move and good news for equities, which benefit as bond yields fall.

The bulls argue that interest rates in the US have peaked. A year ago, the market narrative was for a nasty US recession and higher rates to bite hard. Fast forward 12 months and a ‘soft landing’ for the US economy looks more probable.

Which raises the question: is it time to allocate more assets to bonds?

First, I’m always wary of central bank commentary on economies because it is so often wrong. Exhibit A: the Reserve Bank’s call during COVID-19 that rates would be on hold to 2024. Central bank commentary can be a source of market noise and lead to bad investment decisions.

I’m also wary of jumping onto a changed market narrative. Lots of people are saying US rates have finally peaked after one week of positive news and data. When everybody is saying the same thing about assets, extra caution is needed.

Much can go wrong. Higher inflation remains a persistent threat. It wouldn’t take much for Middle East tensions to escalate further, affecting oil prices. Or for other geopolitical risks to intensify, fuelling concerns of higher interest rates for longer. Reshoring (moving manufacturing back to home countries), the ageing population and labour-market pressures are also pressuring prices.

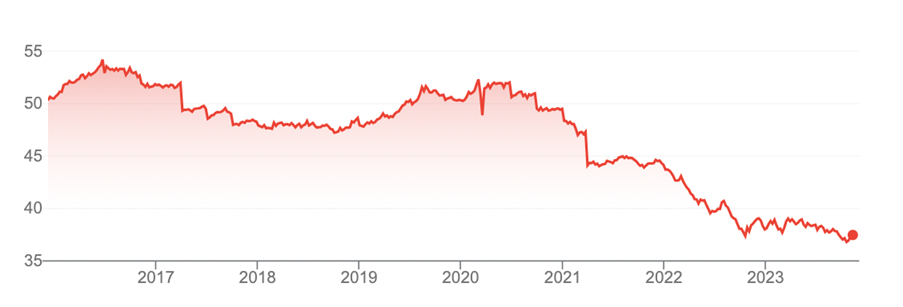

I’m also mindful of history. The US 10-year Treasury yield was in a downtrend for four decades until 2020 (see chart one below) It’s hard to see how a few years of rising bond yields is all we get after a multi-decadal decline in yields.

Chart 1: US 10-Year Treasury Yield

Source: CNBC

The truth is, it’s too soon to know if this is the turning point for US rates. But it’s close enough to a turning point to add more bond exposure to portfolios.

Bonds have been a horrible investment in the past few years. Experts who argued at the start of this year to add bonds to portfolios were too early. They were crunched as bond yields rose and bond prices fell. Few investors thought rates would rise as fast or as far as they did last year.

I favour adding bond exposure to portfolios for three reasons. The first is US rate expectations. I can’t see rates going higher from here without doing immense damage to the US economy. The same is true here. This week’s rate hike, while not surprising, increases the risk of a local recession next year.

The second reason is to increase defensive exposure in portfolios. Yes, falling interest rates will be good for equities – to a point. With so much economic and geopolitical risk, the fear is that economies will slow faster than expected. Some commentators I follow argue the US economy is deteriorating more than official data implies. That’s bad for corporate earnings and equity valuations.

The third is the recent performance of bonds. When an asset class has one of its worst runs in history and delivers negative returns for three consecutive years (which bonds are on track to do by end-2023), it’s time to get interested.

Of course, if inflation picks up again and the US Treasury yield climbs above 5%, new investors in bonds will lose. Also, why buy bonds when some at-call bank accounts are paying over 5%? The answer is expectations of lower bond yields and higher bond prices in 2024, as rates fall.

Those seeking to add bond exposure to portfolios can do so via Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) on ASX. Bought and sold like shares, bond ETFs provide diversified exposure to a basket of local or international bonds. Like most ETFs, they aim to match the return of an underlying index rather than outperform that index.

There are also several quality actively managed bond funds in Australia to consider (I’ll cover them in a later column).

Here are two bond ETFs to consider:

- Vanguard International Fixed Interest (Hedged ETF) (ASX: VIF)

VIF is this market’s largest bond ETF with almost $900 million in assets under management at end-September 2023. VIF invests in around 1,800 government bonds in 35 countries. Its largest exposures are in the US and Japan.

About 90% of securities in VIF range in credit quality from BBB- to AAA. As bond ETFs go, it’s at the lower risk end for those seeking stability from government bonds.

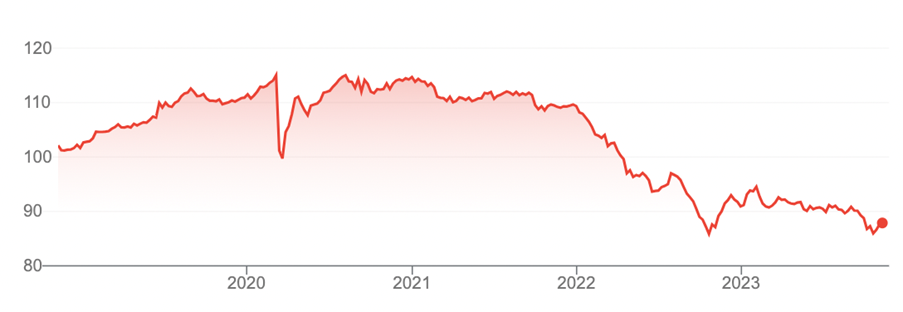

But even VIF has burnt investors in the past few years during the bond rout. It lost 12.69% in calendar-year 2022 and is down slightly this year to end-September 2023. VIF’s annualised three-year return is -5.16%.

In fairness, Vanguard suggests investors in VIF have at least a five-year investment timeframe. Still, losing 5.16% annualised over the past three years (more in real terms after inflation) reinforces the extent of the damage.

VIF’s management fee is 0.2% and it is hedged for currency movements. VIF is solid rather than spectacular, but a reasonable option for investors seeking defensive exposure – and potential upside – after heavy price falls in bond ETFs in the past few years.

Chart 1: Vanguard International Fixed Interest Index (Hedged ETF)

Source: Google Finance

- iShares Core Global Corporate Bond (AUD hedged) (ASX: IHCB)

IHCB provides exposure to a basket of investment-grade corporate bonds across global markets. The ETF had 54 holdings at end-October 2023. About a quarter of IHCB’s holdings are in bonds issued by the largest US banks.

IHCB’s focus on corporate bonds – and its concentrated exposure – means it has a higher risk profile than VIF, which invests in a large number of government bonds. The two ETFs complement each other. Both could be used in the portfolio core for long-term bond exposure and annual income.

Like VIF, IHCB has had a tough few years. It lost 14.8% in calendar-year 2022 and had a small negative return in 2021. IHCB is down slightly year-to-date (to end-October 2023). Also, like VIF, IHCB looks interesting after heavy price falls.

IHCB’s annual management fee is 0.26%. It is hedged for currency movements, meaning investors can gain international exposure to corporate bonds while minimising the impact of Australian-dollar volatility on returns.

Chart 2: iShares Core Global Corporate Bond (AUD hedged) (ASX: IHCB)

Source: Google Finance

Tony Featherstone is a former managing editor of BRW, Shares and Personal Investor magazines. The information in this article should not be considered personal investment advice. It has been prepared without considering your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on information in this article consider its appropriateness and accuracy, regarding your objectives, financial situation and needs. Do further research of your own and/or seek personal financial advice from a licensed adviser before making any financial or investment decisions based on this article. All prices and analysis at 8 November 2023.