If you have a financial adviser, you are likely to be invested in one or more bond funds. And if you haven’t but are trying to run a balanced portfolio, you may also be invested in bonds through a fund.

Bonds are the classic “defensive” asset. Backed by Governments or “blue-chip” corporates, paying secure and reliable income, and with a low risk of capital loss. In multi-asset class portfolios, they are typically negatively correlated to growth assets such as shares or property. That means that their price goes the opposite way to what is happening in the share market – so if shares tank, bond prices will rise. When added in combination with shares and property, a portfolio can be modelled that provides the best possible return for the lowest level of risk.

That’s ‘portfolio theory’ at its most basic – and why bonds (and bond funds) exist in most portfolios.

But in 2022, bond funds have been “clobbered’” – they have lost in the order of 7-10% in value. That might not sound like a lot, but for a “defensive” asset, that’s a big move. Moreover, they haven’t been negatively correlated to the share market – rather, they have been going in the same direction as the share market, largely down.

Below are the charts of two representative bond funds. While both are passively managed exchange traded funds, actively managed funds haven’t fared much better.

The first is Vanguard’s Australian Fixed Interest Index ETF (VAF), which mirrors the broad universe of Australian government, semi-government and investment-grade corporate bonds. It has lost 8.7% in 2022.

Vanguard Australian Fixed Interest Index ETF (VAF) – 2022 YTD

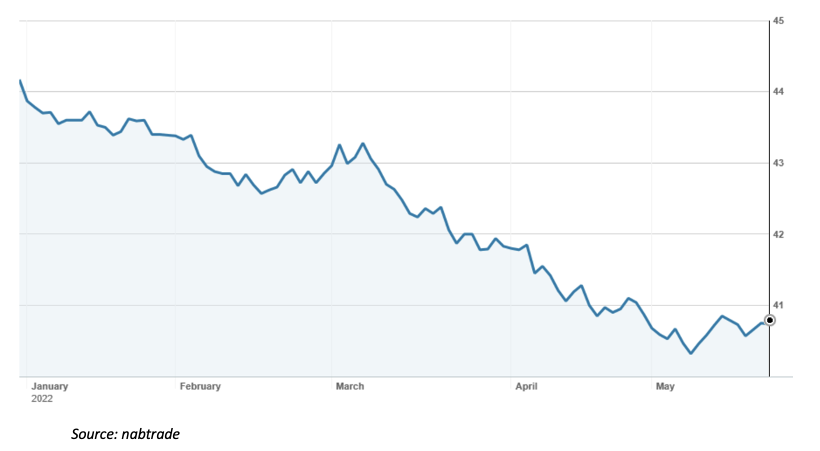

Its international cousin, the Vanguard International Fixed Interest ETF (VIF), which tracks a global index of government and investment-grade fixed interest bonds, has lost 7.6% in 2022.

Vanguard International Fixed Interest Index Hedged (VIF) – 2022 YTD

Behind these falls is the worldwide movement in bond yields as Central Banks turn their attention to fighting inflation. This is best illustrated by the global benchmark bond, the US Treasury 10 year bond, which started the year yielding about 1.5% pa and blew out to over 3.0% a couple of weeks back. It has since eased to yield 2.75%.

US 10 year Treasury Bond in 2022

The big debate in markets is whether inflation is transitory and will ease later this year, or is structural and more permanent. Those in the former camp say that the “black swan” of the Ukraine war and its impact on energy and food prices, plus temporary supply chain pressures as the world emerges from the Covid pandemic, are largely responsible. If a peaceful settlement can be negotiated and supply chain pressures ease, inflation will fall.

The inflation and market bears argue that the Central Banks are behind the ball game. They let their quantitative easing (effectively money printing) programs run too long, and combined with government stimulus, the world has had a massive “sugar hit”. While the Ukraine war has exacerbated the problem, inflation was already on the rise before the conflict broke out. Only rapid action to raise interest rates sharply will curtail the inflation bogey.

And if there is really one “bogey” word for the bond market, that is “inflation”. Combine that with the end of QE (quantitative easing) and the opposite (QT or quantitative tightening) commencing, Central Banks are becoming sellers of bonds and increasing the supply. That’s why bond yields have surged higher.

When bond yields rise, the prices of older bonds fall to make them more attractive to buyers. They find an equilibrium so that a buyer is effectively indifferent to whether they buy a new bond paying a higher interest rate, or an older bond paying a lower interest rate, but which can be purchased for a discount to its ultimate maturity value. And of course bond funds, which revalue their bond holdings daily at the current market yields, fall in value.

But it is not all bad news for investors in bond funds because the funds are now re-investing into higher-yielding bonds. Investors can expect to see higher income distributions going forward.

What’s in store for the bond market?

The bond market will continue to be “obsessed” about inflation, so until there is data to suggest the peak has been reached and Central banks have acted appropriately, it will be on edge.

But there are signs pointing to a steadying in bond yields. Firstly, the markets have priced in very aggressive action by the Central Banks. In Australia, the market is expecting the RBA to lift the cash rate from 0.35% to 2.0% (some say even higher) by year-end. In the US, the Fed Funds rate is expected to increase from almost 1.0% to about 2.5% by December.

Secondly, there is increasing talk of the dreaded ‘R-word’ – recession. Markets of course look well ahead – and they are starting to worry that if Central Banks move too aggressively on interest rates and rattle consumers, spending will fall and the economic growth will grind to a halt. In a recession, inflation and bond yields typically fall.

Finally, the rise has been so rapid that bonds are starting to look attractive. Whereas there wasn’t much incentive to invest in a bond at a yield of 0.10% pa (until late last year, the RBA as part of its QE program was standing in the market and buying bonds out to 3 years at a yield of 0.10% pa), investors can now get close to 3% pa on a 3-year government bond.

And bond funds?

Bond funds look more interesting – certainly a lot better value than they did a few months back. While it is too early to conclude that yields have peaked, my sense is that they are in “nibble territory”. Investors thinking about low-cost index funds could consider VAF or the iShares equivalent, IAF. There is also a plethora of actively managed bond funds, including the ASX quoted BNDS from Betashares.

Term deposits may be a safer bet. Shorter in duration (less interest rate risk, but more re-investment rate risk) and potentially government-guaranteed, Judo Bank (amongst others) is paying 3.0% for 1 year. AMP Bank’s 2-year rate of 3.65% pa looks enticing.

Important: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. Consider the appropriateness of the information in regards to your circumstances.