For many investors, the biggest killer of investment returns is market noise. They make bad decisions by responding to the herd’s latest view on an asset.

Consider China. A few weeks ago, bad news on China was deafening. The country’s economy was stalling as its property sector faltered, youth unemployment ballooned, and consumer confidence waned.

If you believed some commentators, China’s economic miracle was over. Hopes of a strong bounce back in China after COVID-19 were dashed and geopolitical tensions with the West added to the uncertainty. China’s faltering currency and waning global demand for its goods further weighed on sentiment.

Last week, China reported that retail sales and factory output in August grew faster than markets expected. The narrative switched from unrelenting doom and gloom to talk that China’s economy could be stabilising. Suddenly, the market thought China might be less of a drag on global growth than it feared.

China’s news underpinned the Australian equity market’s rally last Friday. A recovering China is good for commodity prices and the resource sector. It’s especially good for a market like Australia.

So, what should investors make of this news? Should they increase their allocation to Chinese equities within the global equities part of their portfolio?

On the first question, it will take a lot more than a few positive data points to confirm China’s economy is stabilising. Investors are often sceptical of Chinese data, particularly when the country needs to report good news.

Longer term, China faces immense structural challenges that will not resolve quickly. They include excessive investment in China’s property sector; its ageing population; youth unemployment and geopolitical tensions with the West that will affect trade and investment with China.

Nevertheless, on the second question of country weightings, I think there’s a case to add China exposure to portfolios. I stress this strategy suits more experienced investors and should be done cautiously, modestly and in the context of a balanced portfolio.

For all the gloom, it’s worth remembering that China’s economy will grow 5.2% this year as consumption improves, forecasts the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Stronger growth from China this year was a key theme for the IMF in May in its revised World Economic Outlook.

Also worth remembering is the herd’s propensity to overstate and amplify bad and good news these days, thanks to social media and the internet. There was likely too much pessimism about China’s economy a few months ago.

What matters most is valuation. That is, whether asset prices have sufficiently factored in news about China’s economy.

The FTSE China 50 Index, a key barometer of large-cap Chinese equities, lost around 19% on a calendar-year basis in 2021 and 2022 (in US dollars). Over five years, the index has lost 5.4% annually (to end-August).

Nobody knows for sure how China’s economy will perform in the next 12 months. But I prefer to put new money to work in losers from the previous decade rather than the stars. Often, capital chases the best ideas that everybody is talking about, only to burn investors at the top. They overlook the losers, just as they have bottom-quartile valuations after heavy price falls.

For clarity, I don’t suggest readers should load up on Chinese equities after recent positive news on its economy. It wouldn’t surprise to see some of these gains given back in the next few months as data disappoints.

But the best time to buy is usually when assets are horribly out of favour; when the market herd has an extremely negative view; when everybody is investing the same way on an asset; and when good news is overlooked or discounted too much.

China has lots of problems. But it’s also the world’s second-largest economy and its economic model might not be quite as ‘broken’ as markets assume.

I prefer using Exchange Traded Funds on ASX for Chinese equities. Bought and sold like shares, ETFs provide diversification and index exposure. Investing in China is risky enough without trying to punt on individual securities.

Here are two China ETFs to consider:

- iShares China Large-Cap ETF (AUD) (ASX: IZZ)

IZZ tracks the performance of the 50 largest and most liquid companies listed in Hong Kong. About 80% of the fund is invested in consumer discretionary, financials and communication stocks. Less than 3% is invested in Chinese tech.

IZZ has an annualised negative return of 9.17% over three years (to end-August 2023). Over 10 years, the ETF has a 2.86% annualised return. Whichever way one cuts it, investing in large-cap China equities via an index has disappointed.

Investors who choose funds solely on past performance will find little to like about IZZ. But contrarians who know that the best time to invest in a quality fund is after a longer period of underperformance might see things differently with IZZ.

iShares notes that IZZ might not be appropriate for investors with a short investment timeframe or who seek a whole portfolio solution. IZZ suits long-term investors seeking capital growth with a very high risk/return profile.

For most growth investors, only a fraction of their portfolio should be allocated to Chinese equities, as part of their global equities allocation.

Caveats aside, IZZ traded on an average trailing Price Earnings (PE) multiple of 11.1 times a price-to-book ratio of 1.36 times at end-August 2023. These are attractive valuation metrics compared to Western markets, although they come with higher risk, including regulatory and sovereign risk.

IZZ is unhedged for currency exposure and its annual management fee is relatively high for an ETF at 0.74% (that reflects the additional complexity of investing in Chinese equities).

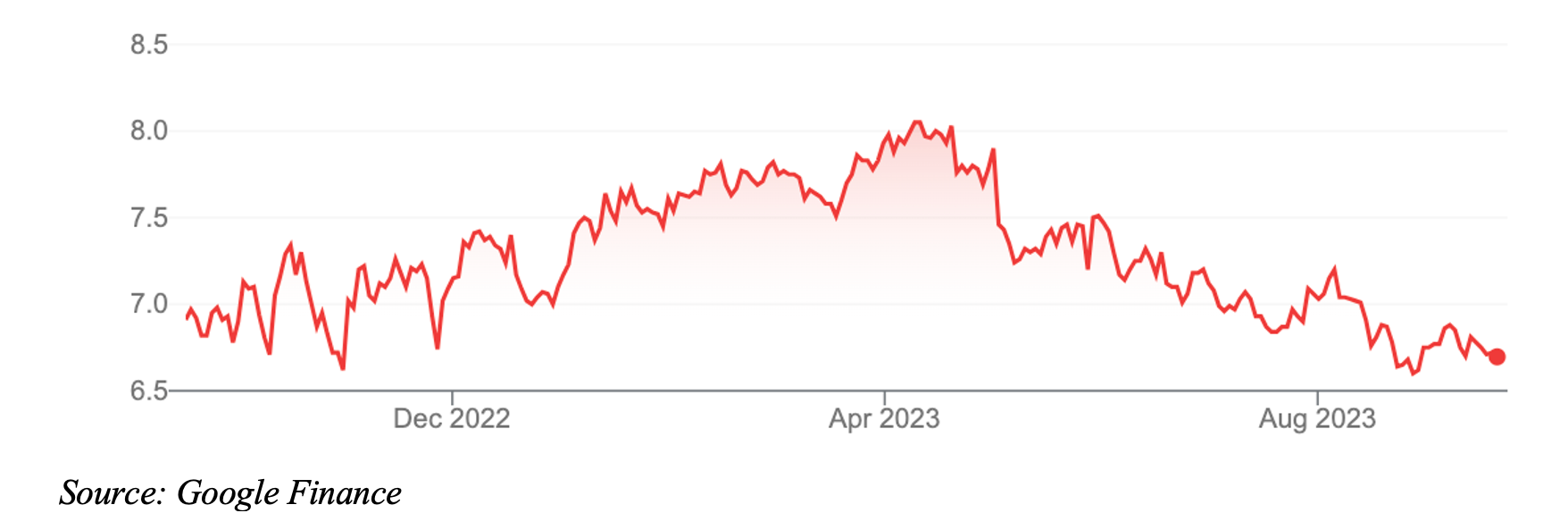

Chart 1: iShares China Large-Cap ETF (AUD) (ASX: IZZ)

- VanEck China New Economy ETF (CNEW)

The VanEck China New Economy ETF is another option on ASX for China equities exposure. CNEW holds 120 stocks across a range of industries. Food, beverages and tobacco, consumer durables and biotech make up almost half of the ETF by sector.

CNEW is a smart-beta ETF. Through a rules-based approach, it tries to find Chinese companies that offer the best growth according to Growth At a Reasonable Price (GARP) attributes. CNEW’s underlying index weights company prospects according to growth, value, profitability and cash flow. CNEW is also equally weighted, meaning no stock can dominate the ETF.

CNEW has a negative annualised return of 10.1% over three years to end-August 2023. Also, CNEW returns can be volatile. Its best quarter (1Q19) returned 36.5%. Its worst quarter (1Q22) lost 18.3%. This is not an ETF for conservative investors.

Experienced investors who want more concentrated exposure to the Chinese growth sector, such as healthcare, consumer staples and consumer discretionary, will find CNEW a useful tool for their portfolio. For all the current gloom, the middle-class consumption boom in Asia still has decades to run as more people join the middle class in Asia and their spending patterns change.

CNEW’s annual management fee is 0.95%. Like IZZ, CNEW is unhedged for currency movements, meaning there is an additional layer of currency risk.

Of the two ETFs, I prefer IZZ, principally because I want broad index exposure to Chinese equities, rather than trying to pick sector or company winners.

Chart 2: VanEck China New Economy ETF (CNEW)

Tony Featherstone is a former managing editor of BRW, Shares and Personal Investor magazines. The information in this article should not be considered personal advice. It has been prepared without considering your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on information in this article consider its appropriateness and accuracy, regarding your objectives, financial situation and needs. Do further research of your own and/or seek personal financial advice from a licensed adviser before making any financial or investment decisions based on this article. All prices and analysis at 20 September 2023.