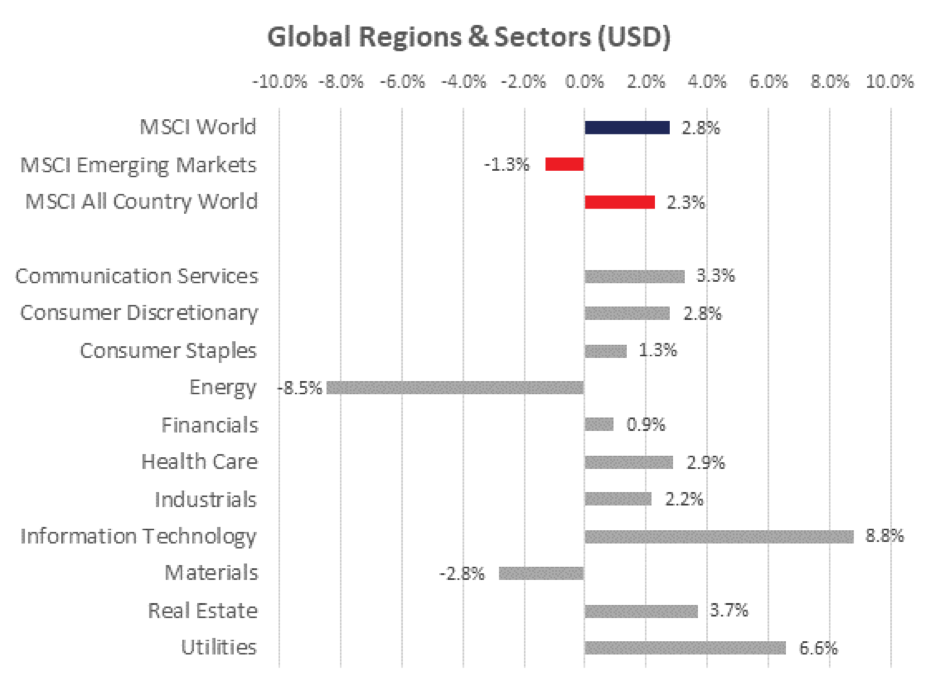

In observing the divergence of calendar year-to-date returns between certain sectors and countries, I believe it is fair to say that the market right now is being driven by big picture macro considerations more so than bottom-up fundamentals. The table below represents the calendar year-to-date return of the MSCI World and its various constituent sectors in US dollars. (I’ve opted to use US dollars, since the weakness of the Aussie dollar in recent weeks skew the results somewhat).

Source: MSCI, FactSet. Year-to-date returns as at 11 February 2020.

What has been in favour are safe havens (like Utilities or Real Estate) or sectors that can grow under their own steam – largely the Information Technology and Communication Services sector (where the majority of the large internet platforms reside). The more cyclically sensitive sectors – Industrials, Financials, Materials and Energy – have lagged, and substantially so in the case of the latter two. Understandably, this is related to the impact the coronavirus outbreak in China might have on global demand for commodities. Given how sensitive many emerging markets are to commodity exports, it’s no surprise that developed markets (and the US in particular, where the economic data remains very robust) has done substantially better over the very short run. US bond yields have also retreated, as investors seek a calm port in the storm, with the result that long duration equity assets have done very well indeed. The divergence in returns is wide, to put it mildly.

This poses a tough question to long-term investors who have disproportionately benefited from this move over the past few weeks: should I sell out and rotate to out of favour sectors or stocks? It’s a high-class problem to have, and one that I believe should be approached rationally.

As a starting point, I think one should recognise that such a question is effectively driven by the fear of avoiding a near-term market correction. In this regard, I’m reminded of the wisdom of legendary investor Peter Lynch: “Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.”

The essence of Lynch’s investment approach was to stick to finding high-quality companies within your circle of competence (“invest in what you know”) and owning them for the long run. He popularised the idea of the looking for ideas by observing how you, your friends or your children spend your time or money, and then inverting from there to find investment ideas. This approach saw him identify many ‘ten-baggers’ – a stock that appreciates to be worth 10 times the initial price paid. A return profile like this was only possible by remaining invested, despite the pain of inevitable short-term market volatility. How did he accomplish this? By knowing what he owned and tuning out the noise of speculation about interest rates, the future direction of the economy or the stock market.

If one takes a dispassionate view of the last few weeks in markets, some companies have probably run a touch too hard for non-fundamental reasons (although most of the current market leaders reported very strong results in January). Is that reason enough for no longer wanting to own them? Not to the investor who takes the perspective of a business owner. Companies that can compound their invested capital and deploy it at attractive rates of return will always remain good long-term investments.

The best starting point is to have a good understanding of one’s internal appetite (and financial capacity) to deal with the potential pain of seeing markets sell off over the short term. In behavioural finance, there is the well-known concept of ‘loss aversion’. Essentially, humans feel a 5% ‘loss’ (even if only on paper) twice as keenly as a 5% gain. We are hard-wired to want to avoid the pain of experiencing losses – and yet, equity markets are volatile by default, so losses are virtually guaranteed.

How do you address this? By being psychologically prepared to endure the pain and having a very clear understanding as to why an investment in a particular company is held. Selling a stock purely due to a rapid decline in the market price is likely to lead to poor long-term investment outcomes. (Conversely, never buy a stock unless you know what fundamental reason would make you sell it.)

Most people would be able to live with a 10% sell off, while a 20% decline starts seeing panic creeping into their thinking. Anything approaching the 30% or more mark sees the ‘get me out no matter the price’ mindset come to the fore – yet this is precisely the wrong moment to capitulate. Again, quoting Lynch: “When [corrections] start, no one knows. If you’re not ready for that, you shouldn’t be in the stock market. The stomach is the key organ here. It’s not the brain. Do you have the stomach for these kinds of declines? And what’s your timing like? Is your horizon one year? Is your horizon ten years or 20 years? What the market’s going to do in one or two years, you don’t know. Time is on your side in the stock market.”

The above is not to say ignore valuations. Given the current risk/reward trade-off, some modest profit-taking may be sensible, but that’s a very different response to selling out entirely and rotating away from high-quality businesses.

Successful long-term investing requires the understanding that one will have to live through short-term volatility. Owning companies that generate excess returns on capital on a sustainable basis means they can weather volatility or economic headwinds. As Charlie Munger says: positive and negative surprises are not equally distributed across good and bad companies. Good things tend to happen to good companies. Don’t sell a good business if it’s pushed on a bit too hard over the short term.

I hope Sir Winston Churchill will forgive my paraphrasing, but at this given moment in markets, it seems appropriate to misquote him: buy and hold can feel like the worst strategy, except for all the others.

Important: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. Consider the appropriateness of the information in regard to your circumstances.