A recurring column theme this year has been to ensure portfolios can withstand higher market volatility and profit from it. Over several columns, I have outlined why markets will be more volatile this decade as powerful global tailwinds turn into headwinds.

Start with inflation. For more than three decades, the world had falling inflation, interest rates and cost of capital for companies. Now we have higher inflation and interest rates than we have been used to – a trend that will persist this decade.

After enjoying a long period of energy abundance and lower energy prices, the world faces higher energy costs amid decarbonisation and the transition to renewables. Higher energy costs are a brake on economic growth.

Since the 1980s, the world benefitted from hyper globalisation. A larger supply of labour and manufacturing capacity in China and other developing countries reduced the cost of goods and eased inflation in the West.

Now we face an accelerating period of deglobalisation as multinational companies produce more goods at home to reduce global supply and, in some cases, avoid higher US tariffs – a trend known as ‘reshoring’.

Also, trade liberalisation that flourished over the past few decades has been replaced by the prospect of higher US tariffs and US isolationism, to a degree.

Moreover, a period of relative geopolitical harmony since the Cold War ended (in terms of large-scale wars) has been replaced by the Russia-Ukraine war, the Israel-Iran war and broader conflict in the Middle East, not to mention the threat of China invading Taiwan later this decade.

Perhaps the biggest shift has been the US retreat from its role of world hegemon or unipolar power, and the emergence of a multipolar world where other major powers dominate their region.

Sadly, the world seems to be rapidly dividing between G7 countries (the West), authoritarian states (Russia, China, Iran and North Korea), the Global South and ‘connector’ countries non-aligned to great powers, or neutral (think India, Indonesia and Brazil). This promises more geopolitical volatility and risk.

I could provide other examples of major shifts in global megatrends occurring this decade. I suspect historians will look back on the 2020s as the great decade of ‘pivoting’ when huge trends, such as globalisation, changed course. With that comes share market volatility, threats and opportunity.

For investors, the challenge is understanding how this period will play out and the best themes for portfolio exposure. This is no easy task, but essential for long-term investors and contrarians like me who favour thematic investing rather than direct stock picking, which is becoming increasingly harder to get right.

I have outlined several such themes this year, notably defence, commodities and the rotation out of US equities into European and Chinese equities. Defence Exchange Traded Funds have been among the top ETFs this year.

Commodities

Commodities are intriguing. I have made the case over the past year to increase exposure to resource companies, principally on expectation of growing supply constraints. Simply, it’s getting harder and costlier to develop mines.

Conflict in the Middle East – and Trump and China using commodity supply as bargaining chips in trade warfare – add to the risk of commodity underinvestment and scarcity, which in turn supports higher metal prices in the long term.

Commodities suddenly look more strategically valuable, not only on economic grounds but in terms of national security, diplomacy and trade leverage. Trump made that point this year when he noted the dominance of foreign copper producers as a growing national security threat for the US.

Proposed higher US tariffs on steel, aluminium and other commodities further reinforce the strategic value of commodities – and complicate matters for resource companies with investment and location of new projects.

Like defence companies, major resource companies could be key long-term beneficiaries of this period of heightened geopolitical and economic volatility. Both themes should feature in portfolio global equity allocations.

If a new commodity super cycle emerges (some resource bulls argue we are in the early stages of one), higher portfolio exposure to resources will be important.

Gaining exposure

Copper remains a preferred commodity, principally due to long-term underinvestment in new copper projects, and also because of rising demand for copper, a key metal in electric vehicles and other renewables technology.

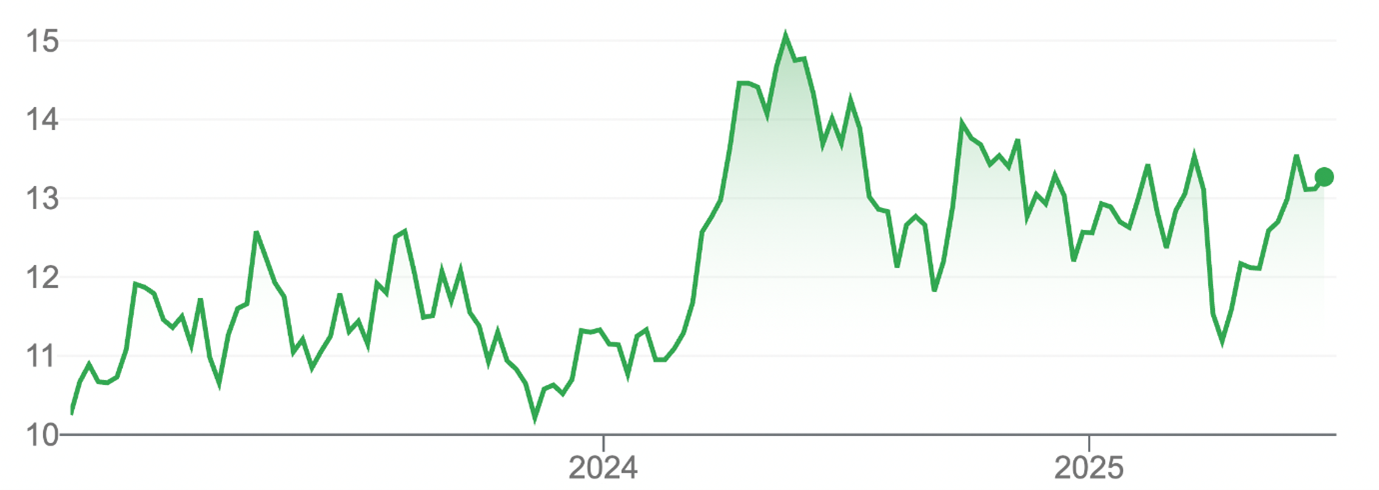

The Global X Copper Miners ETF (ASX: WIRE) provides exposure to global copper companies via ASX. WIRE holds 40 of the largest copper companies, including First Quantum Minerals, Freeport-McMoRan and BHP Group.

WIRE has lost 10.5% over one year to end-May 2025, amid broader underperformance in the resource sector. Over three years, the index WIRE tracks (the Solactive Global Copper Miners Total Return Index) has an annualised return of 8.2%, badly underperforming the MSCI World Index.

At its current price, WIRE could be an interesting opportunity for long-term portfolio investors who want greater exposure to commodity supply constraints (and higher metal prices), principally through copper.

Copper’s exposure to decarbonisation and clean-energy infrastructure, and its broader leverage to global economic growth, are other attractions.

Chart 1: Global X Copper Miners ETF

Source: Google Finance

While most resource focus has been on hard commodities, it’s worth considering how heightened geopolitical volatility will affect soft commodities.

The US has proposed higher tariffs on several agricultural imports. China and other countries retaliated with higher tariffs on US agricultural exports. Soft commodities, too, have been embroiled in global economic warfare.

As with hard commodities (metals), geopolitical uncertainty could constrain investment in new agricultural projects, affecting prices. As geopolitical risks rise, food security and agricultural independence are becoming even bigger issues.

The Betashares Global Agriculture ETF (ASX: Food) provides exposure to 60 of the world’s largest agriculture companies. Almost half of these companies are in the US, meaning they could benefit from favourable US government policy that encourages greater domestic food production and less reliance on imports.

At end-May 2025, FOOD traded on a forward PE of 13 times and price-to-book ratio of 1.4 times – attractive valuation metrics compared to many other sectors.

Like the copper WIRE ETF, FOOD has performed poorly over one year, returning just 1.1% to end-May 2025. That follows slightly negative total returns for FOOD in calendar-years 2024, 2023 and 2022.

As global demand for agriculture rises, and as the sector faces growing supply constraints, FOOD has underperformed. That could change in the next few years as agriculture, like metals production, plays a bigger role in geopolitics.

After several years of falls, FOOD looks like it is turning the corner and could be an ETF to watch in 2025 and beyond.

Chart 2: Betashares Global Agriculture ETF

Source: Google Finance

Tony Featherstone is a former managing editor of BRW, Shares and Personal Investor magazines. The information in this article should not be considered personal advice. It has been prepared without considering your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on information in this article consider its appropriateness and accuracy, regarding your objectives, financial situation and needs. Do further research of your own and/or seek personal financial advice from a licensed adviser before making any financial or investment decisions based on this article. All prices and analysis at 24 June 2025.